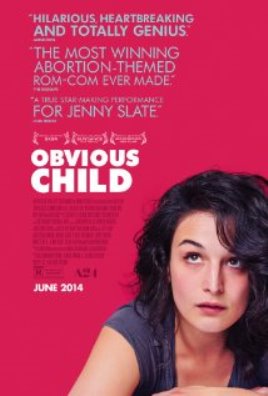

Addressing Abortion: Obvious Child Plays It (Mostly) Cool

To be honest, this began as a review of OBVIOUS CHILD, the poised to be indie breakout from writer/director Gillian Robespierre and starring Jenny Slate. Yet when I started to write it, I ended up with some 1000 or so words about the role of abortion in the film before I had really even touched the movie itself. So, here’s the solution: this piece, an exploration of abortion’s “role” in the film, and this other piece, a more “proper” review of the film.

From the start, it is important to define what kind of movie OBVIOUS is. To its credit, the movie is about people, not abortion. It tells a story in which abortion comes up, it is not an “issue” movie (save one scene but we’ll get there) about abortion. Instead of unfurling as a thesis about a woman’s right to choose, it takes the issue and normalizes it. Issue films are more than ok, but I like the idea of a movie that can be “about” abortion without being, you know, ABOUT abortion.

The reality is, abortions happen. At most recent available count, approximately 16.9 out of every 1000 woman between the ages of 15 and 44 have had the procedure done. These are not large numbers but they are not non-existent either, indicating the women having abortions are not aberrations, hedonists, monsters, or whatever label you would like to hang on their neck. To pretend otherwise is to deny some of the actualities of our world. It is nice, and past due, frankly, to have a film that exists in that reality. Women have unwanted pregnancies for any number of reasons and sometimes those women seek abortions.

In line with that, there is never any question that Donna Stern (Slate) is going to make the choice to end her pregnancy. The movie does not bother to pretend as though this is a “will she or won’t she” tale. There are never attempts to throw in a scene of her wavering—one could imagine her having to hold someone else’s baby or flipping through a photo album of her first days in a different kind of movie—to drum up drama. It does mean, plot-wise, there’s not much doing here, but the alternative is pretty cloying and, to be honest, ugly.

Nellie (Hoffman) and Donna (Slate) enjoy some good dressing room sitting. (picture from article.wn.com)

However, the film is not flippant about a woman’s choice either. It does not act as though having an abortion is a guaranteed arduous, scarring experience, but it also does not deny that it can be an emotional experience to go through. Donna’s best friend Nellie (Gaby Hoffman) has no regrets about her abortion, taking place sometime in her teen years, but she occasionally remember and shed a tear for the terrified woman she was at that time. Donna never doubts the choice she has made, but she is still anxious about how others will receive the news, still emotionally raw about everything swirling around her as the days tick by to her appointment. It is a decision with consequences, just not the false consequences anti-choice advocates repeatedly try to make “common knowledge.”

Also in the film’s favor is that it makes it clear that choosing to terminate or not terminate a pregnancy is a woman’s rights issue, it does not freeze men out of the proceedings. Max (Jake Lacy), Donna’s one night stand, is present at the hospital, is supportive, and while clearly unnerved by the revelation that she is a.) pregnant and b.) ending the pregnancy when he first hears about it, he never questions her choice, gets into the whole “my kid too” argument, or is otherwise depicted as being possessive, demanding, or denying Donna’s agency. Fellow comedian and close friend Joey (Gabe Liedman) is similarly present, available, and supportive without trying to influence her decision.

Donna (Slate) and Max (Lacy) talk books, cardboard. (pic from sundance.org)

Still, there is, as alluded to above, a bum note in the film. Amongst the people Donna tells is her mother Nancy (Polly Draper)who turns out to also have an abortion story of her own, about the time before abortions were made legal by Roe v. Wade. It is the movie’s one moment of unambiguous messaging which, while noble and understandable, does somewhat crush the small film under its weight. For me, however, this was easy enough to overlook. I like Sorkin, my capacity for preachiness is fairly high.

My problem with the scene was fueled more by the fact that it meant all three women who are characters in the movie (there are three medical professionals who speak but none reoccur and two speak no more than two lines) either have had abortions or about to have one. It’ not necessarily a problematic choice, but it does add to the feeling of the smallness of the world and overturns some of the film’s realism by subtextually suggesting every woman Donna has a relationship has made the choice to have an abortion at some point.

Second, in part because the film has no woman who has not gone through it who’s depicted as supportive of Donna and in part because of the nature of the mother/daughter relationship until Donna’s confession, there is an almost implicit suggestion that Donna’s mom can be supportive because she’s been there too as opposed to she is supportive because she is Donna’s mom and loves her regardless. From a scripting/plotting standpoint, it reads as a lack of trust in the audience and/or the characters to believe in someone who could be supportive without having traversed that road themselves. It’s not a massive thing, perhaps, but it nagged at me for the rest of the picture.

It is also worth noting, although it did not raise my antennae until later on, that, if the film takes place now or now adjacent, the story Donna’s mother tells her does not fit because of when New York legalized abortion and when Roe v. Wade made it legal countrywide. Again, it is not a massive deal, but it speaks to the way in which the film is stretching and pretzeling itself to be both a slice of life, matter of fact picture and also connect with the country’s unfortunate history as it comes to abortion.

This amount of criticism does not mean I did not think the film did not do a smashing job overall of depicting the process of terminating a pregnancy. In addition to the characterization mentioned above, Robespierre conducts some subtle scenes that capture, I imagine, some of the surprising (or sadly unsurprising) moments that come along the way towards—and just after—having an abortion. The conversation with the clinic official who wants to talk about “all” your options even as you say you have already decided, the literal monetary cost, the strange mix of discomfort and connection that comes in the recovery room after as the women silently wait in pink hospital gowns for the go-ahead to leave. Robespierre’s lens and Slate’s performance excel at these scenes, these almost silent moments frozen on screen.

The predominant lack of histrionics or melodrama about the choice itself does not necessarily “trump” some of what I felt did not work, but it does outweigh them. It is not a flawless film, but it is a good one. Very good at points. And with the right of choice being increasingly vilified, misrepresented, and legislatively reduced, that is no small thing. By treating it largely as a big but not earth shattering choice, the film captures how important abortion truly is.